4 Comments

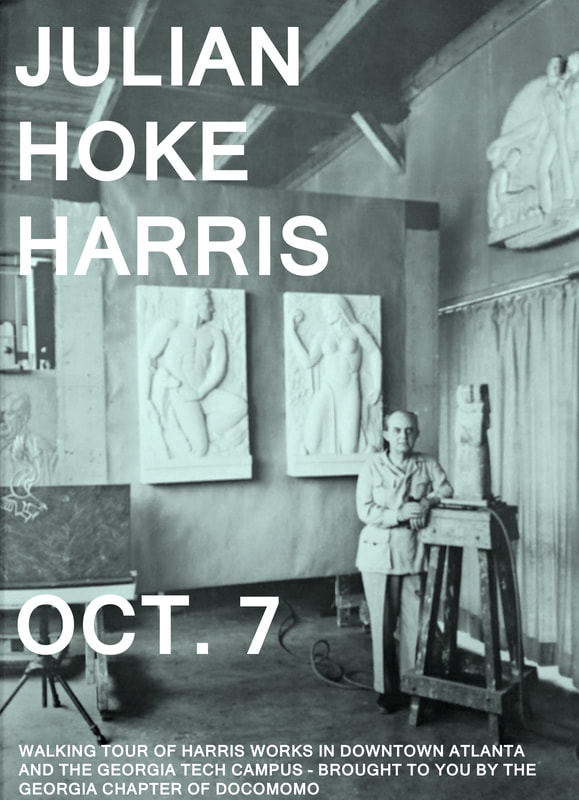

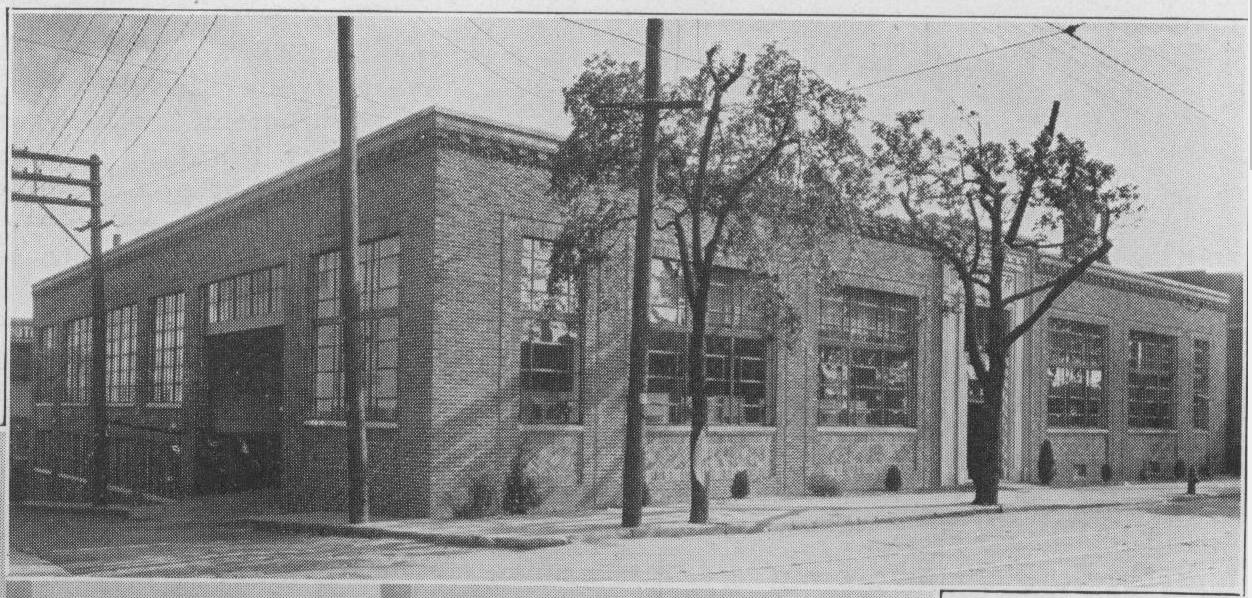

According to Fulton County, the Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness building needs $6-10 million to correct “substantial infrastructure issues.” Rather than complete these renovations, Fulton County has moved out of the building. It appears the property is being sold to Grady. Docomomo has learned that the building is slated for demolition. The Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness was designed by the firm McDonald and Company and was dedicated in 1959 (the building was not occupied until 1961). McDonald and Company (McDonald & Co.) was an Atlanta-based architectural and engineering firm practicing in the early to mid-twentieth century. The firm’s best known work is the 3rd Union Station, built in 1930. The marble and limestone, third Union Station (the second Union Station was demolished shortly after the third was built and the first was destroyed during the Civil War) was built facing Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta. The building is said to have been the first “to take advantage of air-rights above State-owned railroad tracks” (Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, 1880s-1930s). The third Union Station is said to have been the work of architect Howard C. McLaughlin, who was with McDonald and Co. at the time. The building was demolished in 1972. If Union Station had survived, it would today be facing the Five Points MARTA station and the Atlanta Constitution building. McDonald and Company is also credited with the Meuller Lofts building in the Castleberry Hill neighborhood of Atlanta. The building was a warehouse and showroom for Mueller Company, a plumbing fixture supplier. McDonald and Co. also designed the 1929 Paramount Theater (now Davis Theater) in Montgomery, Alabama. Affixed to the Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness building are two metal bas-reliefs by artist Julian Hoke Harris. The pieces are titled; "Keeping Away Death" and "Keeping Away Old Age" and are also known, according to Harris, as "Preventative Medicine" and "Geriatrics." Harris received his Bachelor’s degree in architecture from Georgia Tech in 1928. He later graduated from the Pennsylvania Institute of Fine Arts in 1934 and then took a job teaching at Georgia Tech, where he remained for 36 years. Harris’ sculptures are said to be featured on more than 50 buildings in the southeast, including Georgia’s State Agricultural Building and State Office Building. According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum; “He also designed and executed more than twenty medallions, including Georgia Tech’s Monie A. Ferst Medal (a national award that recognizes excellence in advancing research through education), the bicentennial medal for the state of Georgia, and President Jimmy Carter’s official inaugural medallion.” Harris died in 1976. (For a period biography see the Rotarian, Nov 1964 Vol. 105, No. 5, pp. 38-41) The Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness building (also called the Aldridge Health Center) was identified in the 2013 Downtown Atlanta Contemporary Historic Resources Survey Report as a National Register of Historic Places eligible property.  This March, we lost the old Georgia State Archives building; designed by A. Thomas Bradbury in 1964. Atlanta, a city whose last major expansion coincided with rise of Modernism, is lucky to have had a handful of great Modernist architects living and practicing within the city. Bradbury was certainly one of them – Born in 1902, Bradbury graduated from the Southeast’s top architecture school, the Georgia Institute of Technology, or “Tech” to locals. While Georgia Tech can be said to have spawned the “Atlanta School” of architectural design, Bradbury tended towards New-Formalism (and, interestingly, may be responsible for why most outside of Atlanta aren’t familiar with the Atlanta School). Bradbury’s work embraces symmetry and proportion. His use of marble for his cluster of state buildings downtown is a modern interpretation of the White City of the Chicago World’s Fair. He also emphatically embraced romanticism; building a Gone With the Wind-style mansion for the Georgia Governor and a Moorish temple for the Shriners. The Old Archives Building was certainly his most iconic. The Archives was sited on a piece of land at the intersection of our busiest interstates, which are predictably right in the center of Atlanta. A small rise makes the site visible from every direction and from quite some distance. Bradbury, rather than concealing the function of the building, put the archival block up on a pedestal for all to see. The two story base with wrap-around columned portico and formal entrance at the piano nobile, gave the building its southern charm; a welcoming entry and a shaded porch. The slabs of honed white Georgia marble wrapping a windowless towering block, placed the building thoroughly within the Modern period. However, nearly 20 years ago and only 34 years from when it was completed, the Archives was vacated for a new facility in the exurbs. The ‘old’ building had not been maintained and was beginning to exhibit problems typical for its age. Also, it was running out of room for physical archives, while simultaneously not being equipped to handle digital information storage. Instead of rehabilitating the building, the state decided to abandon it. Despite its vacancy, the building has proudly occupied its site for 20 years, a glistening white “ice cube” that has captured our imaginations in several big movies. One of the last films shot there, Ant Man, predicted the fate of the Archives when they (spoiler alert) digitally exploded it in a final climactic scene. In reality, the archives was imploded early on a Sunday morning in front of a crowd of mourners.

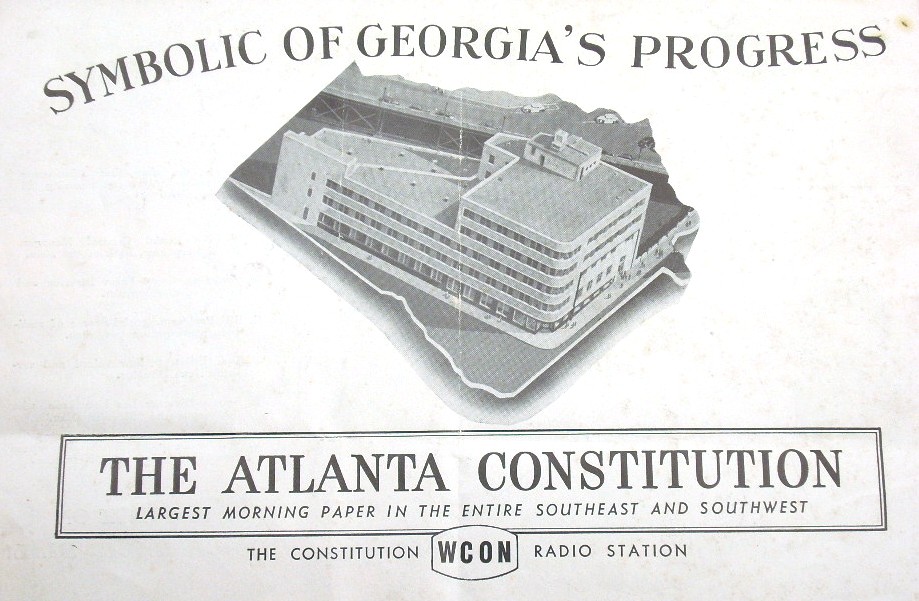

Atlanta Constitution Building, 1948-1953. (Special Collections Department, Georgia State University Library) Atlanta Constitution Building, 1948-1953. (Special Collections Department, Georgia State University Library) A CONTEXT FOR THE CONSTITUTION BUILDING The 1940s were a considerable period of growth in Atlanta. In the years leading up to World War II, the downtown area (roughly defined by the corridor of blocks stretching from North Avenue south to Memorial Drive) continued to grow as the city's major commercial and business district. At the center of this growth were the blocks straddling the railroad gulch, also referred to as the “Heart of Atlanta” due to their proximity to the “Zero Mile Post” which marked both the Southeastern terminus of the Western and Atlantic railroad and the city's earliest settlement. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the area held its place as a civic center. New development in West End and an increase in urban housing density from multiple projects by the Works Progress Administration contributed to the area’s success. Shops and business along Forsyth, Whitehall, and Mitchell Streets continued under the period of Jim Crow legislation and represented a crossroads for many white and black residents of Atlanta. Atlanta's two train stations were the source of much of the district’s vitality. The railroad boom from the 1920s left its mark throughout the city, most notably the eight trunk lines coming under the viaducts to the Union (constructed 1930) and Terminal (constructed 1905) Stations. Terminal Station, located at the intersection of Spring and Mitchell Streets, served the Central of Georgia, Atlanta & West Point, Seaboard, and Southern rail lines. Passengers from near and far walked down Mitchell Street to shop at the many stores on the southern side of the gulch, including Rich's, Bass's and the Kress ten-cent store. The Central of Georgia line promoted “Rich's Shoppers Specials” to entice riders into the city. During the years of World War II, the Five Points intersection was the rallying point for bond drives and other public demonstrations, as it had been during the previous war. The commercial district also provided entertainment and distraction for GIs on leave to the city. After the war, and as GIs returned, the city rebounded from its wartime rationing of goods and services and assumed an even greater vitality. Broad Street was known as a printing street and was home to many of the city's journals, including the Atlanta Constitution, the Atlanta Journal, Christian Index, Sunday Gazetteer, Sunny South, Weekly Post, as well as several printing firms and binderies. In the first week of 1948, the Atlanta Constitution moved from its location next to Rich's Department store to a new facility across the street. It was the first building designed expressly for a newspaper in Atlanta since the Constitution's previous building opened in 1884. Conceived at the end of an era, the design combined a range of details and expressed a turning point in American architecture. The façade's horizontal bands of windows, curved corners, and sleek stone sheathing contributed to the streamlined aesthetic popularized by the Art Moderne style. But the building's dynamic relation to its triangular site and the continuation of the brick banding throughout each elevation bore the influence of both European Modernism and the progressive designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, notably the widely acclaimed Johnson Wax Administration Building (1936-1939). The significance of the new building was underscored during construction in 1947 when the newspaper's reporters ceremoniously placed pennies in the building's wet concrete. The building's cost, reported as $3,000,000, was a sizable sum for the time. Expenses for the modern plant included “new presses, steel desks, marble corridors and every mechanical contrivance for publishing a modern newspaper in the shortest possible time.” Additionally, WCON, the Constitution's new radio station, was located on the top floor of the building. Retail space occupied the building's sloping base level. Windows located along the Alabama Street sidewalk provided the public a view of printing presses located below street level. Upon moving in, Editor Ralph McGill expressed his desire that the Constitution's prestige should grow to match its new home. After relocation of most of the offices to the new facility, local artist Julian Harris began work on a sculptured 72-foot mural above the building's main entrance along Forsyth Street. Harris carved the sculpture in situ, working daily on a scaffold high above the sidewalk. The project lasted over a month and provided a unique live display of an artist at work. The design, developed over the course of a year, recorded the history of the newspaper and depicted reporters, photographers, and printers at work. Also constructed during the same period was the Rich's Store for Homes. Constructed opposite Rich's main building and adjacent to the Constitution Building, the new store capitalized on the post war demand for houses and provided a wide array of furnishings and domestic goods. The dislocation of the new building inspired the construction of an innovative four-story steel and glass bridge over Forsyth Street to connect the two stores. Dubbed the “Crystal Bridge,” and designed by the Atlanta firm of Toombs and Creighton, it is regarded as one of the first Bauhaus-inspired designs in the South. Transportation improvements continued to affect the downtown district. Begun in 1949, the development of a master urban plan led to the construction of the Metropolitan Expressway System to link the inner city with the national system of interstate highways. In addition, a commercial expansion was planned for downtown, but little progress was made by the end of the year. Such results became symptomatic of the growth trend towards the suburbs. By 1952, through annexation, the city limit had grown to an area three times its size in 1950. During this period, home construction soared in Atlanta's outlying areas and the number of autos surpassed 150,000; each reflecting an enormous shift in personal mobility and residential options. In 1950, James C. Cox bought the Constitution and merged it with the Journal under the name of Atlanta Newspapers, Inc. Although news and editorial operations of the two newspapers were kept separate, the change did result in the consolidation of many operations, leading to Georgia Power Company’s leasing of the building. The building achieved a new significance as the company’s main office and the location where many Atlantans paid their electric bills. In 1953, Atlanta was still the busiest railroad city in the south, servicing 83 passenger trains a day. However, as the expressway neared completion in 1955, daily passenger traffic reduced to 58 trains. The threat to downtown's commercial district was most evident in the 1956 plans for a new shopping mall in the burgeoning area of Buckhead. Opened in 1959, Lenox Mall provided for the exodus of Atlanta residents outside the historic city limits, and as a result, the downtown business district began to suffer. Construction activity did continue downtown, primarily limited to new office space. In 1957, an expansion of the capital complex was begun, and in the following year the Fulton National Bank moved into their 25-story tower-the tallest constructed since the William Oliver Building in 1930. As the center of commercial activity moved northward in the 1960s and 70s, Plaza Park and the rest of the business district to the south of the gulch fell into neglect. In 1960, Georgia Power vacated the Constitution Building and was the last long-term occupant. Further signaling the abandonment of the area, in 1972 both of Atlanta's downtown train stations were demolished, marking the end of private passenger service as AMTRAK took control of the diminished rail lines. During the following two decades, substantial changes would occur: Businesses move further north, suburban office parks grow in significance, and intercity rail service declines. In the immediate area, the once vibrant shopping district is now mostly a memory. The new Sam Nunn Federal Center now occupies the former Rich’s store, the MARTA Five Points station serves to connect two main train lines, and the nearby Underground Atlanta development continues to search for a successful mix of entertainment and shopping. Studies for a multi modal passenger terminal to serve planned commuter rail lines, AMTRAK, and bus service have focused on properties adjacent to the MARTA station for a number of reasons. Existing rail lines, access to MARTA, and the expanse of valuable undeveloped property known as the “gulch” have contributed to this focus. These plans assume demolition of the Spring Street Viaduct and the Atlanta Constitution Building would be required to make way for a new terminal structure, never considering adaptive use of the historic structures as an alternative. Long-range plans have proposed dense development in and over the historic “gulch.” Ultimately, plans for a new multimodal terminal remain unfunded. Currently funded plans include only one commuter line (a 26-mile Lovejoy-Atlanta line), planned to start operation in 2006. Associated with this is a pedestrian link allowing passengers to walk below Forsyth Street to the MARTA station. Although these plans assume demolition of the Constitution Building, they do not include construction of a terminal as anticipated in the 1995 Memorandum of Agreement. Jon Buono, Thomas Little ©2004 DOCOMOMO US, Georgia Chapter, Inc.

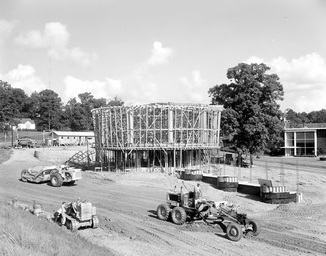

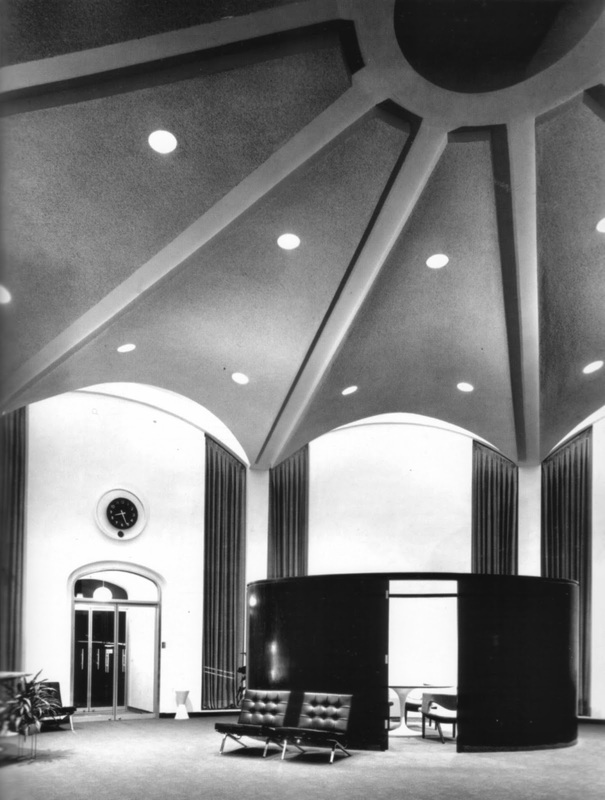

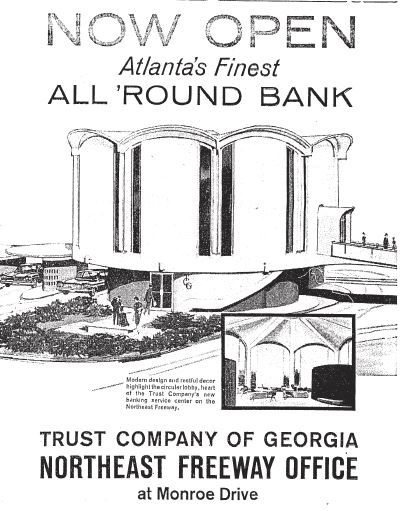

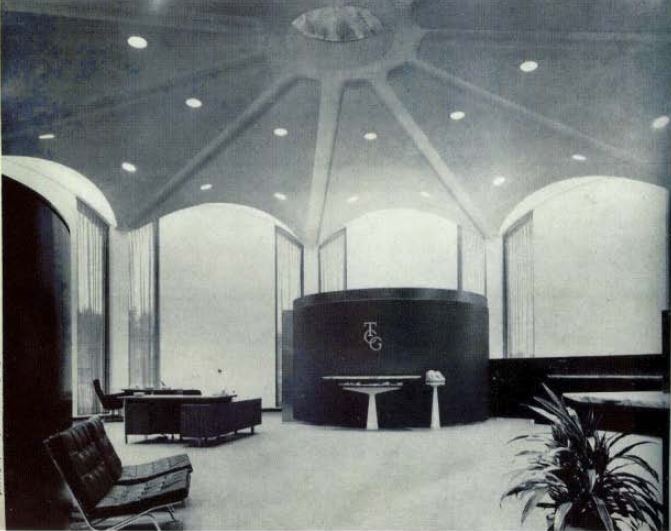

The architectural design of banking institutions prior to World War II depended heavily on classical motifs. Temple-fronted banks of stone and brick evoke a sense of timelessness and sturdiness: characteristics aptly suited for the institutions entrusted with the life savings of their customers. However, beginning perhaps with the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society headquarters designed by George Howe and William Lescaze (1926-1932), banking institutions began to deviate from these classical forms and some even fully embraced the Modern. Changes to all aspects of banking, from the increasing use of automobiles to changes in banking regulations, “helped transform an institution that represented tradition in all facets to one that embodied a new American vision: the modern, progressive bank building as a powerful image-making and passive advertising tool.”1 This modernization expressed itself no better than in the form of the drive-through teller and the car-centric bank branch. When the Trust Company of Georgia began planning for a new bank branch in the early 1960s, expression of modern ideals in bank architecture was reaching its peak. The selected site for the new branch building was a perfect expression of the needs of the modern banking customer: easily accessible, and highly visible, to commuters on the busy Northeast Expressway. For the design of the new building, the Trust Company hired Abreu and Robeson, with Henri Jova as lead architect. “Because of the site,” explains David Reinhart, “it was hard to figure out which way to orient the building. [Jova] decided a round building would be a solution. A round building would relate itself to the entire intersection of the Interstate and Monroe Drive.”2

An array of three drive-through teller stations, round, of course, with overhanging round roofs, cascade west from the main building. To the east, prominent curved signage is mounted from towering trident prongs. In 2000, SunTrust Bank, the result of the Trust Company’s merger with SunBanks of Florida, sold the property. The bank was purchased by Inman Park Properties but sat vacant, so the Atlanta Preservation Center declared the building endangered in 2003. The bank building was soon adapted for restaurant use, opening in 2005 as Piebar, a retro-modern pizza restaurant. In 2006, the building was chosen by the American Institute of Architects as one of Atlanta’s best buildings of the previous century: one of five buildings representing 1956-1965. In 2007, the Atlanta Urban Design Commission recognized Piebar with an award for adaptive use. Piebar closed in 2008 and was replaced by Eros, a tapas lounge. Inman Park Properties lost the building in foreclosure in 2009, prompting the Atlanta Preservation Center to again declare the building endangered. Subsequent years have seen the tenant change again from Eros to Ixtlan Ultra Lounge and now Cirque, a daiquiri lounge. The building sits within the Atlanta BeltLine’s zoning overlay district and was identified in early surveys as a significant building. In 2011, the BeltLine master plan recommended that the building be designated a local landmark. 5 A proposal to demolish the building was presented to the BeltLine Design Review Committee in July 2016. Broward Development would like to replace the historic bank building with a 5-story self-storage facility. The property is located at 2160 Monroe Drive in Atlanta. Docomomo US/GA is currently exploring options to save the building.

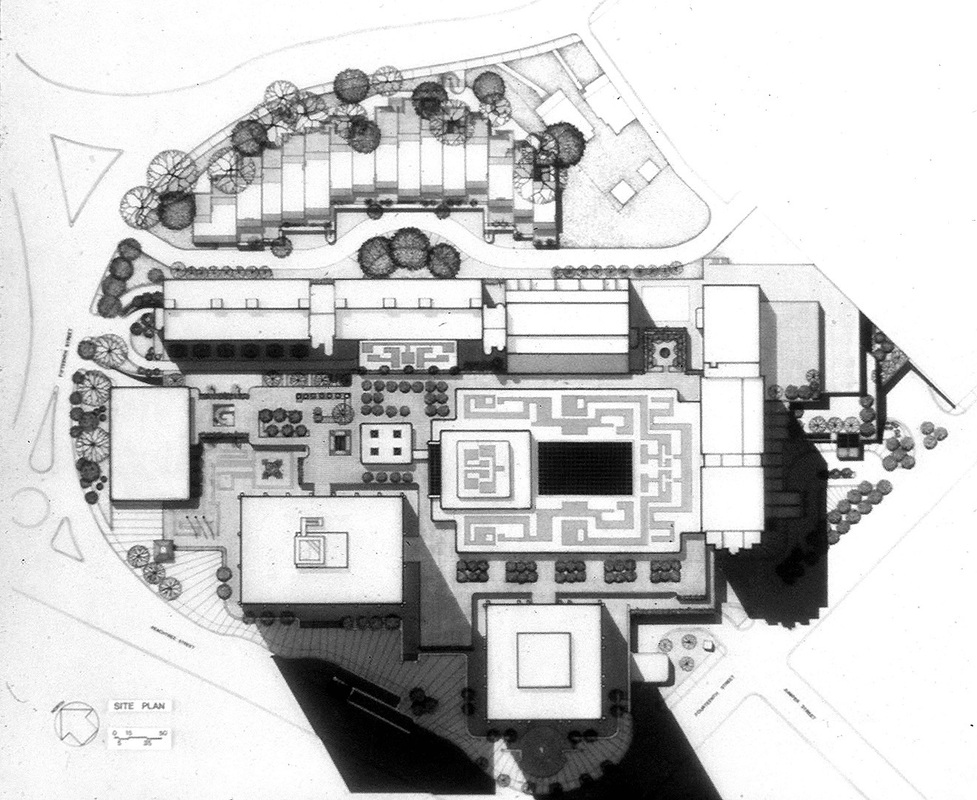

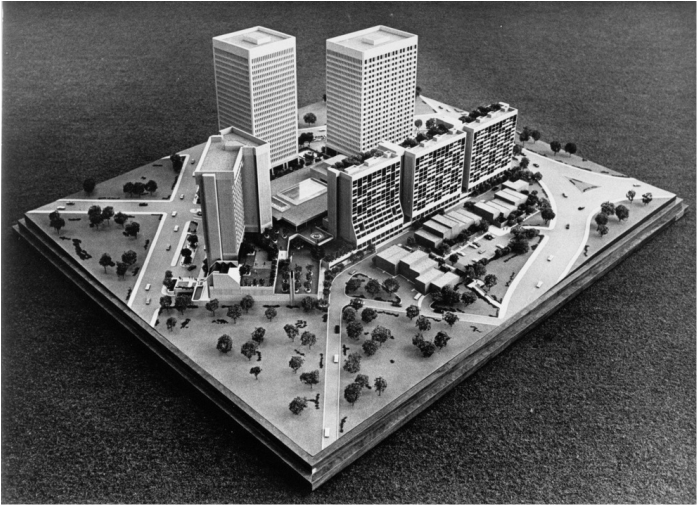

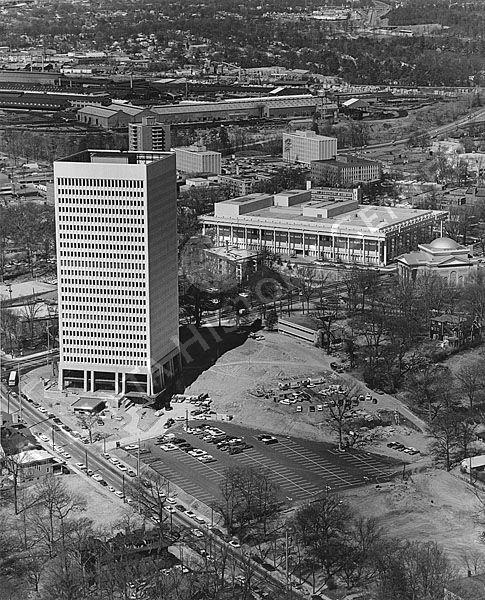

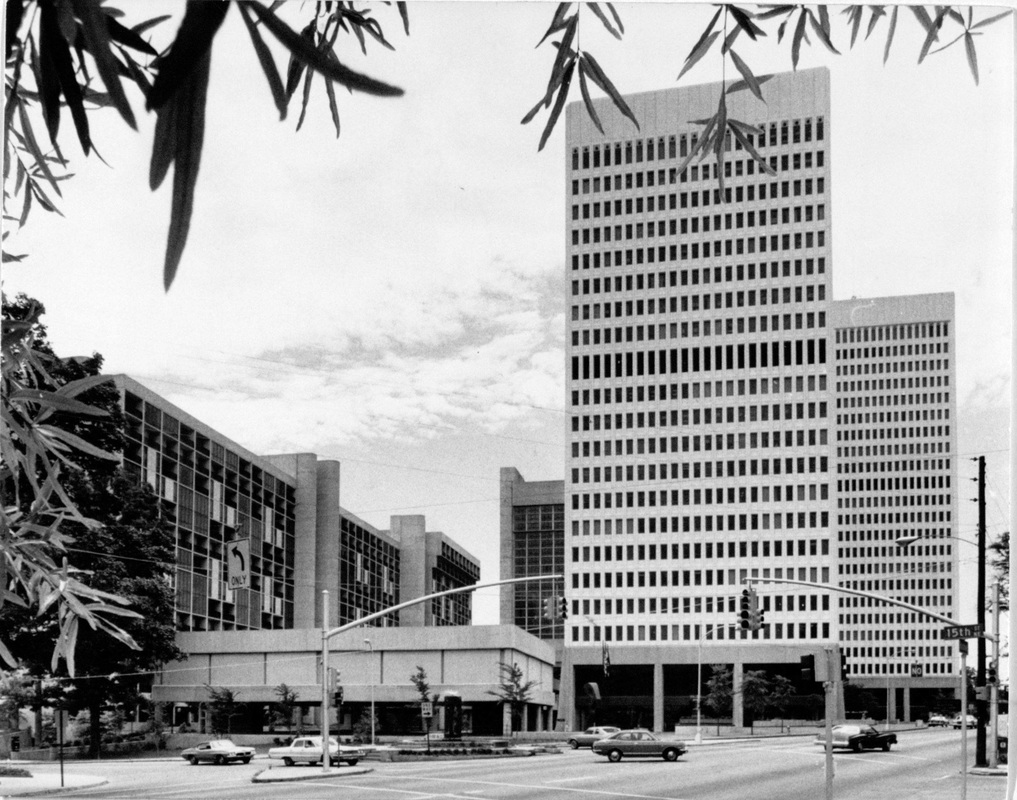

"This is a new concept in the South... It's a good concept, really, in the whole country and the world". This was Jim Cushman's reaction to the architect’s presentation of the site plan for what was to become the first mixed-use development in Atlanta and the southeast, Colony Square. The year was 1967. Now, nearly 50 years later, "The Sequel" is being launched by Colony Square's new owners, North American Properties. NAP is still developing plans for the re-envisioned complex and has been soliciting input through the hashtag #reimaginecs. But back when the hashtag was simply known as the number sign, Cushman was soliciting financing for the then uncharted live-work-play concept. Jim Cushman was an Atlanta developer, who, with Ward Wight, had built the office towers around Lenox Square, Lenox Towers and the Paces Place residential development, one of the first condominium projects in Atlanta. He later went on to found his own development company to develop Colony Square. The architect behind the "good concept" was Henri Jova, a rising star in Atlanta architecture whose career started in New York working with Wallace Harrison. Jova formed a firm together with John Busby and Stanley Daniels around the Colony Square project which became their first commission. Paul Friedberg, best known for his design of Jacob Riis Plaza in New York City and Peavy Plaza in Minneapolis, was brought in as landscape architect. Midtown was an interesting bet for this "micropolis"; the only other development in a modernist style was the Memorial Arts Center (Amisano, 1968), now known as the Woodruff Arts Center. The Colony Square site placed the development along Peachtree Street, between Portman's energetic downtown developments at Peachtree Center and, to the north, a rapidly developing Buckhead, spurred on by the construction of Lenox Square (Amisano, 1958) ten years earlier. By 1969, the first Colony Square tower was complete. The rest of Colony Square was largely completed by 1972, despite a looming bankruptcy filing from Cushman. The complex included over 800,000 square feet of office space divided between the two twenty plus story towers, 467 condominium units of Hanover House and Colony House, a 143,000 square foot retail mall with ice skating rink, 1,700 underground parking spaces, a free-standing two-story retail building, and a 467-room hotel. Town homes planned for the 15th Street-facing side of the property were never realized and that portion of land was eventually sold and developed separately. During the early 1980s, the ice skating rink, which occupied a portion of the atrium space of the retail mall, was removed and replaced by a 'food court'. Other changes included replacement lighting, alterations to the atrium roof, removal of the drive-through banking structure (now a pocket park along 14th), changes to finishes and interior cladding, and expanding and enclosing more of the commercial and public spaces adjacent to the food court. The most significant changes included severing of the hotel from the food court and the shrinking of what was a major entry from Peachtree to the mall to accommodate a less than sensitive new restaurant structure. Friedberg's landscape, which included curvilinear cast-in-place planters integrated into the site, sunken porches, and plazas, remains largely unchanged. In the last decade the intersection of 15th and Peachtree Streets was realigned. A fountain that once occupied a traffic island formed by the curving turn lane of Peachtree Street to 15th Street, which followed an old trolley route, was incorporated into a small corner park.

Docomomo US/GA supports a revitalized Colony Square that retains and uses as a design asset the original features that give the property its architectural character. The mixed-use concept, so cosmopolitan in 1960s Atlanta, continues to be relevant, special and inspiring today.

2nd Stop: Peachtree Center Station - exiting the trains, attendees are wowed by the exposed rock walls of the platform before heading up the world's tallest escalator. The firm Toombs, Amisano, Wells designed the station, which was completed in 1982. Back on the street, introductions are made to our very own (and potentially endangered) Breuer Library, as well as the collection of Portman buildings comprising Peachtree Center.

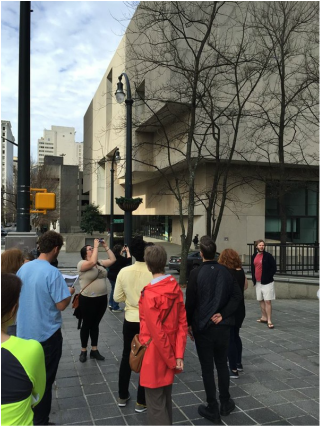

3rd Stop: North Avenue Station - the third and final stop brings attendees to the artful North Avenue station, designed by Jova, Daniels, Busby and completed in 1981, and above ground to view several more fine examples of Modernism, including another Jova Daniels Busby design: the 1968 Life of Georgia Building. We look forward to expanding this tour with more stations and offering it again for next year's Phoenix Flies. But before that, we will be offering our annual docomomo tour in October. Stay tuned! 5 March through 20 March, 2016 the Atlanta Preservation Center will be hosting their 13th annual Phoenix Flies event.

"Atlanta’s historic built environment of buildings, landscapes and neighborhoods is an integral part of the City’s culture and economy. The Phoenix Flies Celebration provides an opportunity to learn about, celebrate and strengthen these assets to the benefit of all." This year the Georgia Chapter of Docomomo US will be hosting several tours of MARTA stations. Tours will be held on Saturday March 5th and Saturday March 19th, both beginning at 10am and running about an hour and a half. Tours will begin at the Forsyth Street entrance to the Five Points station. If you would like to volunteer as a tourguide, researcher, guide editor, or support, please go to our Google Groups page and request to join. We are organizing volunteer efforts through VolunteerSpot and will provide a link through the group page. We love photographs of interesting expressions of modernism! Especially around the Atlanta area. But we love data even more. Do you have an interest in Modernism, a camera, and the time to do a little research?

We have started developing an interactive map of Modern resources in Georgia and would love to use your contributions. Imagine how quickly we could build a geolocated database of all of Georgia's Modern standouts. Imagine the benefits of that data. Please help us grow the map of places by taking a photograph and writing a short description and/or history of the place. Please include with submissions the address and current status. Email information to [email protected] Thanks! |

Docomomo_US Georgia ChapterMoving Modern Forward Archives

September 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed